The Maturation of the eSports Industry: Loot Box Regulation and Beyond

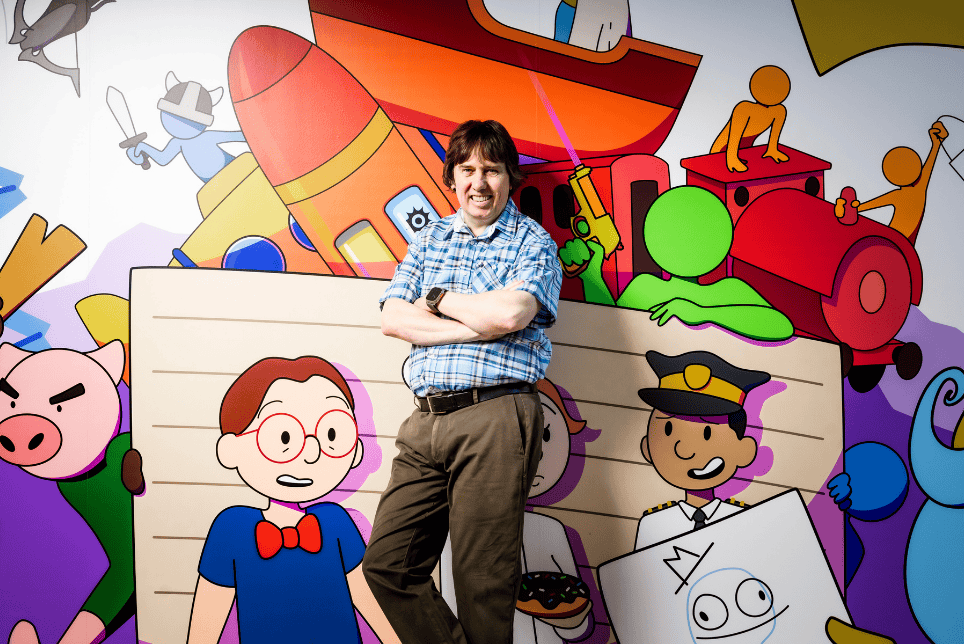

Harry Lang is the VP of Marketing at Kwalee. He started his career in integrated marketing agencies before spending the next seventeen years marketing online and mobile gambling brands.

In 2020 he published ‘Brands, Bandwagons & Bullshit’ a guidebook for young marketers trying to break into the industry.

Three years ago, I wrote an article for Marketing Week highlighting the paradoxical nature of the eSports industry. The crux was that the games industry was growing incrementally in size and reach and yet demonstrating naivety (and, to some extent, arrogance) in some of its actions and behaviours. Loot box regulation became a hot topic during this period. The matter of Loot Boxes epitomized this concern. Last week there was a significant development on this subject, with UKIE and the DCMS announcing 11 new ‘best practice’ Principles on the operation of paid loot boxes in video games, indicating that things are finally changing for the better.

An Age Old Problem

Loot Boxes (also known as Loot Crates to the uninitiated ) are virtual treasure chests containing undisclosed items that can be used within PC and console games, often to customise characters or weapons (for which the items are known as ‘skins’). Initially developed in 2007 for the Chinese game Zhengtu, they were sold to ensure a revenue stream for the game developer, since most Asian players used internet cafes or downloaded the game illegally.

Within a year, Zhengtu Network reported monthly revenues of more than $15m, leading to the trend for game developers and publishers worldwide to release free-to-play games positively drowning in micro-transaction opportunities. The adaptation of loot box regulations and implementations became crucial as the popularity of such mechanisms grew.

In America and Europe, the video games industry (led by the omnipotent Valve Corporation with its Team Fortress 2 game) adopted and adapted Loot Boxes and a proliferation of social gaming brands like Zynga (creator of mega-hit Facebook games Farmville, Zynga Poker and Words with Friends) came to market. These games allowed players to pay in-game through IAPs to progress through levels faster.

The games industry is an innovator by nature, rarely slow to pounce on potential profit, so popular games such as FIFA, Counter-Strike, Battlefield, Call of Duty and Overwatch all adopted their own versions of loot crates.

Soon enough, everyone was at it and the money started rolling in.

Dark markets

‘Skin aftermarkets’ sprung up around 2016, including unlicensed third-party trading and casino-style betting sites. Being unregulated, these betting sites were open to anyone with a Steam account. Worryingly, they were freely accessible to kids.

The government’s response to the alarming ‘dark market’ was anchored on loot box regulation. In 2020, the Department for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport (DCMS) announced it would investigate loot boxes alongside a review of the Gambling Act.

In response to a DCMS select committee report into ‘Immersive and Addictive Technologies’, minister Caroline Dineage acknowledged: “During the coronavirus pandemic, we have seen more people than ever before turn to video games,” and as a result “the government has committed to tackling issues around loot boxes in response to serious concerns about this model for in-game purchasing”.

Unsurprisingly, being a political decision, the next steps involved a call for evidence, contribution to further investigation, research into the impact of gaming, and workshops including representatives from academia and the esports industry.

There’s a 190-year-old giant tortoise called Jonathan living on the island of Saint Helena who moves faster than this.Most professionals I know in the regulated gambling and esports industries were hugely in favour of player protection. As such, we could probably have saved the DCMS and its political overlords some time. Back in 2020, I penned the following as my own interpretation of the Principles required for government mandated regulation:

- Regulate the sale of in-game loot boxes and skins in all esports games

- Implement ‘problem gaming’ protocols in line with regulated gambling policy

- Educate esports players about the risks of problem gambling and offer the required resources to mitigate such risks

- Require skin betting sites to be licensed, with any of the 200+ non-compliant offshore sites being blocked or prosecuted

Most PC and console game development businesses are run by pretty savvy folk. They’ve known which way the wind was blowing for some time and have adjusted their sails accordingly. From 2017, publishers started culling loot boxes from their games, most notably Epic, within what was then the world’s most popular game, Fortnite. In 2019, Blizzard Entertainment removed real-money loot box purchasing from Heroes of the Storm.

The Need for Regulation

While the profitability and allure of loot boxes have been evident to both developers and players for many years, the risks, especially amongst younger audiences, have persisted. Some argue, correctly in my view, that the luck/ win element associated with loot boxes mirrors gambling mechanisms, potentially leading to addictive behaviours for young gamers in the future.

A Closer Look

Formulated by the DCMS’s Technical Working Group, which consisted of a broad spectrum of representatives from the games industry, the new Principles were the result of extensive consultations. Government bodies, industry veterans, scholars, consumer associations, and advocacy groups were all involved, highlighting a collective responsibility in the games community to bolster player protection and enhance transparency around Loot Boxes. The consultation led to the publication of 11 Principles: –

- Technological Controls: Prevent individuals under 18 from accessing loot boxes without parental consent.

- Communication: Promote awareness of these controls, supplemented by a public information campaign.

- Expert Panel: Set up a panel for age assurance to share best practices and liaise with regulators.

- Transparency: Clearly indicate the presence of loot boxes before a game’s acquisition.

- Probability Disclosures: Inform players about the odds of obtaining specific items.

- Design: Ensure loot boxes promote fair play and are easily comprehensible.

- Research: Support a framework for quality research while safeguarding data privacy.

- IP Protection: Counter unauthorised external sales of loot box items.

- Refunds: Implement easy refund policies for unauthorised purchases.

- Information Dissemination: Advance player protections by circulating responsible gaming info.

- Collaboration: Work with the UK Government to assess the effectiveness of these Principles post a year of implementation.

The delivery of these Principles for Loot Box usage signifies an industry becoming more self-aware of its responsibilities – and more prepared to act on them.

A Future Vision

Yes, the DCMS and UKIE are being proactive with their 11 Principles, and yes, those Principles (no matter how overdue) have benefited from significant industry consultation and thus are thorough. The problem lies in relying on execution through self regulation and we can look at similar self regulation in the alcohol industry to see what the future may hold.

Set up in 1989 as part of a campaign to raise awareness on alcohol-related issues, the Portman Group and its members account for the majority of alcohol brands sold in the UK. When they enacted their own Codes of Practice in 1996, they went beyond the expected regulatory Principles of the then government. This wasn’t just the group being conservative – it was to ensure the industry could remain self regulating (and as such, able to operate and advertise) without regulatory intervention. From this, we can see that stringent, well executed self regulation can be beneficial – to an extent.

With Loot Crates, we’ll have to wait and see whether the 11 Principles go far enough (and are adhered to well enough by all game developers in enough markets) to protect kids and ‘at risk’ adults from developing problem gambling behaviours.

If they don’t, the only viable option will be government mandated regulation – which is, in my opinion at least, what should be happening now.

Only time will tell which way this will go.

If you are a game designer, consider applying for a role in Kwalee’s studio, or send us your mobile game or PC Console game if you are a games studio and want an expert partner to help you bring your game successfully to market. You can also follow us on social media to get more game design insights (TikTok | Twitter | YouTube | Instagram | LinkedIn).

Add new comment